COVID-19 Contact Tracing: Privacy Threats and Data Protection Recommendations

Introduction

While many countries across the world begin to gradually reopen their economy, one important question in the minds of many people and organizations is what post COVID-19 normal will look like. It is highly unlikely that we will return back to what life used to be before January 2020! In his recent blog articles titled “Pandemic I: The First Modern Pandemic”, Bill Gates stated that during World War II, an amazing amount of innovation helped end the war faster. He further listed five categories of innovation that can help this generation to return to normal. According to Bill Gates, advances in treatments, vaccines, testing, contact tracing, and policies for opening up economies are the key enablers to stopping the virus and return to business as usual. Currently, many researchers and institutions are working round the clock to develop effective and efficient testing strategies, vaccines, and treatment for COVID-19. In the absence of a vaccine for treating COVID-19, efficient testing strategies and contact tracing will be the most effective methods available for preventing the spread of the virus. It is suggested that if carefully designed and embraced by the majority of the population, contact tracing may suppress the second wave of COVID-19. This blog looks at current technology innovations in contact tracing, privacy threats, and data protection recommendations.

Innovations in Contact Tracing

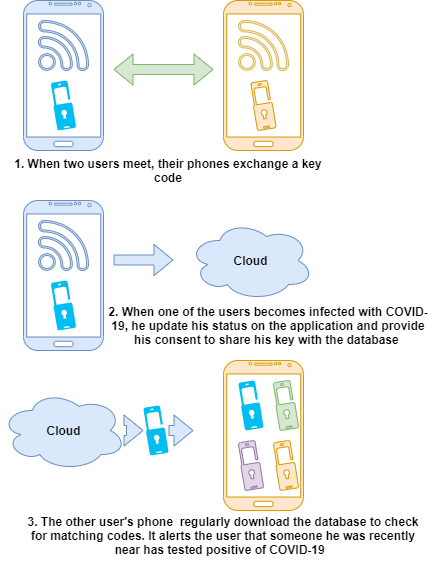

Contact tracing, in public health, is the process of identifying, alerting, and collecting information from people who have been exposed to someone infected with an infectious disease such as COVID-19. Smartphone-based contact tracing applications are designed using Bluetooth, Global Positioning System (GPS), and other mobile network connectivity protocols to track people’s movements. The technology logs every instance a person is close to other people for a specific period. Fig.1 illustrates how the contact tracing works.

Many countries across the world have rolled out a digital strategy for tracking possible coronavirus exposure. The following are a non-exhaustive list of contact-tracing smartphone applications in various countries.

-

In Singapore, the TraceTogether application was recently launched as a supplementary tool for COVID-19 contact tracing. The app utilizes BlueTrace, a protocol for logging Bluetooth encounters between participating devices to facilitate contact tracing.

-

In Australia, the COVIDSafe application was developed to enable health officials to access information about people’s interactions if they contract COVID-19.

-

In Hong Kong, StayHomeSafe application and electronic wristbands are being issued to arriving passengers placed under a two-week quarantine and medical surveillance as part of the country’s effort to reduce the spread of COVID-19.

-

In the Kingdom of Bahrain, BeAware application was launched to help contain the spread of COVID-19 by advancing contact tracing efforts. The app utilizes location data shared by users to alert those at risk and track the movement of those placed under quarantine.

-

In India, the Aarogya Setu application was launched to help track COVID-19 patients and the people they may have come in contact with.

-

In Israel, the HaMagen application was launched to cross-check the GPS history of resident’s phones with historical geographic data of COVID-19 patients from Israel’s Ministry of Health.

-

In the European Union (EU), two COVID-19 proximity-tracing projects have emerged recently. The Pan-European Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (PEPP-PT) and the Decentralized Privacy-Preserving Proximity Tracing (DP-3T). The PEPP-PT project was developed to enable different countries' applications to work together rather than becoming incompatible at each nation's borders. The DP-3T project uses Bluetooth Low Energy on mobile devices and ensures that personal data and computation stays entirely on a user’s phone.

-

In Norway, the Smittestopp application was launched to help the Norwegian Institute of Public Health and other health authorities to limit the transmission of COVID-19. Anonymized data about people's movement patterns are used to develop infection control measures.

-

In the United Kingdom, a group of scientists based at the Big Data Institute at Oxford University have proposed a COVID-19 contact tracing solution that combines a mobile application with public health measures such as physical distancing and widespread testing.

-

In the United State, HealthyTogether is a COVID-19 response initiative by the state of Utah for notifying those at risk. Another initiative in the US is Safe Paths, an MIT-led contact-tracing technology that provides users with information on their interaction with COVID-19.

-

In Canada, the Alberta province has recently launched ABTraceTogether, a smartphone application for identifying contacts of a confirmed COVID-19 case.

Security and Data Privacy Issues

Despite the potential of COVID-19 innovations in contact-tracing, the technology has triggered a debate about data security, user’s privacy, and whether it gives the government extra powers to snoop on people’s privacy. This is because these applications collect sensitive personally identifiable data such as first and last names, phone numbers, addresses, age, location, disease symptoms, and COVID-19 test results. Recently, a rift has emerged among the PEPP-PT project participants who quit citing privacy concerns and lack of proper governance and transparency. The following are some major security and data privacy issues that should be considered when developing a pandemic contact tracing technology.

-

Privacy invasion and unprecedented surveillance: some of the applications are invasive and involve storing user’s GPS logs and location data through scanning Quick Response (QR) codes. Some of the fears are that this could eventually lead to unprecedented surveillance or the establishment of a surveillance state. This is specifically an issue of concern in countries or regions without a comprehensive data privacy law to protect sensitive user data or those who are making the use of the technology compulsory.

-

Bluetooth vulnerabilities: so far, the majority of COVID-19 contact tracing applications rely on Bluetooth connectivity. Attackers may be on the lookout for potential vulnerabilities to steal sensitive user data or launch malware attacks. It is easy for attackers to discover new, previously unknown software vulnerabilities in Bluetooth devices, especially the newer versions. Older Bluetooth devices that use outdated versions of the Bluetooth protocol will likely face the threat of unpatched security holes.

-

Data leakage and breach: data collected in some of these applications are transported to centralized data centres or cloud platforms which are potentially vulnerable to hacking. These platforms are highly dependent on wireless communication and pose a serious risk of data leakage and breach due to hardware or software issues, internal or external means, intentional or unintentional actions, authorized or malicious actors, or natural disasters. Such sensitive data can be used against individuals and states if it falls into the wrong hands.

-

Misinformation: as the world grapple with the COVID-19 pandemic, we also face a deluge of misinformation about the virus on both traditional and social media. Contact-tracing technologies offer opportunities for bad actors to create fear, spread false reports of infection to cause panic, perpetrate fraud and abuse, or spread misinformation.

Data Protection Recommendations

The primary challenge for these technologies remains to secure the privacy of users and local businesses visited by diagnosed carriers. There should be a deliberate effort to discover and map out where sensitive user data generated through COVID-19 contact tracing solutions are stored and develop effective access, protection, and monitoring strategies to safeguard the data and user privacy. Measures should be put in place to ensure that the data collected through these applications are used for COVID-19 contact-tracing and not for any other purpose. The following are some measures that need to be put in place to ensure data security and user privacy when developing or using contact-tracing applications.

-

Transparency and open source adoption: despite moving at speed to halt the spread of COVID-19, essential data governance procedures and established principles of openness and transparency must be intact. The government must be transparent with the information they collect and what they will be used for. User privacy laws must be enforced or enacted. Application developers should test their codes using standard application security testbeds and also make their codes open-source. For example, according to the Australian government, after the pandemic, all information stored in centralized storage will be destroyed and users will be prompted to delete the COVIDSafe application and associated personal data from their phones.

-

Minimization of information collection: the application should not collect sensitive information that might not be relevant to contact tracing. All irrelevant data must be automatically deleted while relevant data must have an expiry date for deletion. For example, Alberta’s ABTraceTogether is based on Singapore’s TraceTogether application. However, according to Alberta Health Services, ABTraceTogether collects less information than any other similar product being used by other jurisdictions to fight COVID-19.

-

Anonymization and decentralization of data storage: personal data should be anonymized and stored locally on users' phones. A limit of storing user’s data and the connectivity mode should be precisely placed. These applications can be secure if the data is localized on users’ devices so that the user can decide whether to handover to the health agency. For instance, ABTraceTogether uses Bluetooth (not GPS). The only information exchanged between users’ phones is a random ID that is non-identifying. The collected data is encrypted and held on the user phone for 21 days. If the user tests positive, they can consent to upload that record to AHS to reach out to the affected contacts.

-

Oversight by an independent party: to ensure there is a balance between responding to the pandemic and protecting key human rights, oversight by an independent party and/or an expert review should be carried out before deploying the technology to the general population.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 crisis has triggered a lot of innovations. However, until vaccines and treatment become available, global recovery and opening of economies will depend on the success of current efforts in testing and contact tracing. This blog has presented a list of contact tracing applications in several countries. It also reports on issues of invasive privacy and data security being echoed across the world because of the ad hoc nature of solutions geared to halt the spread of the disease. While this technology will strengthen and speed up the contact tracing process, privacy issues must be considered very important by all stakeholders. There should be a balance between responding to the pandemic and protecting key human rights.

-

Regulators and government must ensure transparency and accountability about how these applications work and what is being done with sensitive user data. This will earn users’ trust and will lead to widespread adoption of the technology.

-

Application developers must ensure that sensitive user data are secured and destroyed once the pandemic is over.

-

Cybersecurity centers, training institutions, and researchers need to be involved in making sure that these applications meet specified minimum data security and privacy standards before being launched.

Overall, the technology should be voluntary, collects minimal information, use decentralized storage of de-identified Bluetooth contact logs, and allows individuals to have total control of their data.