Explainable Malware Detection with Graph Neural Networks

In the high risk setting of malware detection, transparency and explainability are critical components of trustworthy prediction making. However, for deep learning-based detection methods such transparency is often hindered by model complexity. In this blog post, we explore the application of Graph Neural Networks in malware detection and focus on their unique explanatory capabilities.

Traditionally, malware detection has often relied on cryptographic hash-based signature detection methods. Here, signatures of many known programs are compared to the signature of an unknown program (i). If a match is found, the unknown program is said to be malicious (ii). However, while this paradigm is effective and efficient in practice, it suffers from a major conceptual flaw. Often, it is assumed that if no malicious matches are found, the unknown program is benign (iii). This incorrect assumption allows malware authors to trivially defeat signature-based methods, e.g., MD5, SHA256, etc., that are sensitive to minute perturbations, i.e., flipping, at minimum, one bit to induce a non-match [1]. To address this, techniques such as SSDeep [2] offer relaxed signature-based matching. However, with the advent of Large Language Models (LLMs), with proven automatic software development capabilities, it is likely that LLM-generated malware variants will be used to defeat these solutions, though this is speculative.

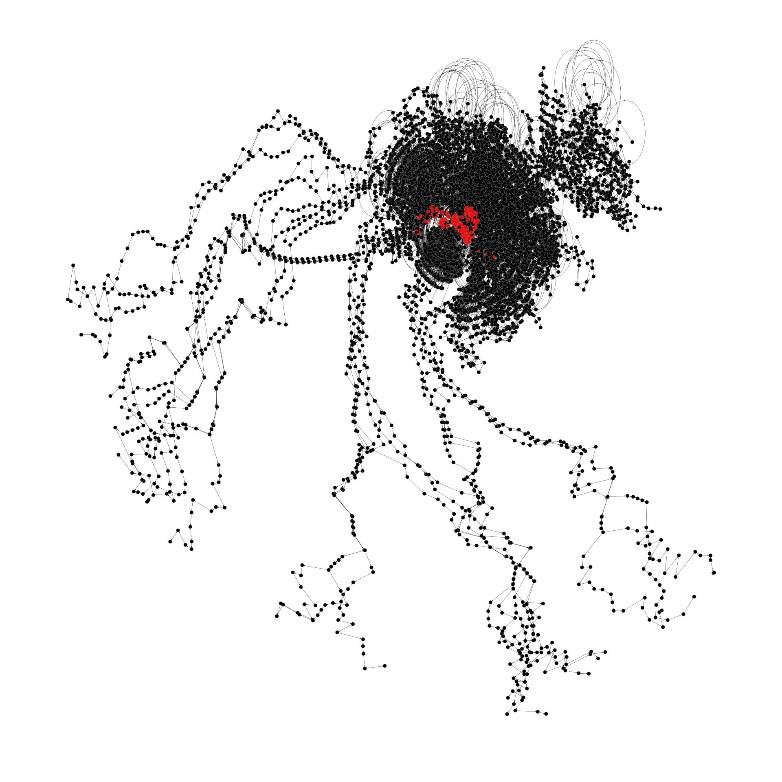

To address these challenges, Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) based methods, such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), have begun to play a vital role in malware detection [3, 4]. Importantly, GNNs are able to learn complex patterns from existing benign and malicious programs that consider their structure and behavior. This highlights a superior capability of GNNs to make generalized predictions on unseen in distribution samples. To accomplish this, GNNs are trained in a supervised setting using graph data representing program flow, i.e., Control Flow Graphs (CFGs) and Function Call Graphs (FCGs), extracted from many known malicious and benign programs dynamically and statically [5, 6].

How Do GNNs Work?

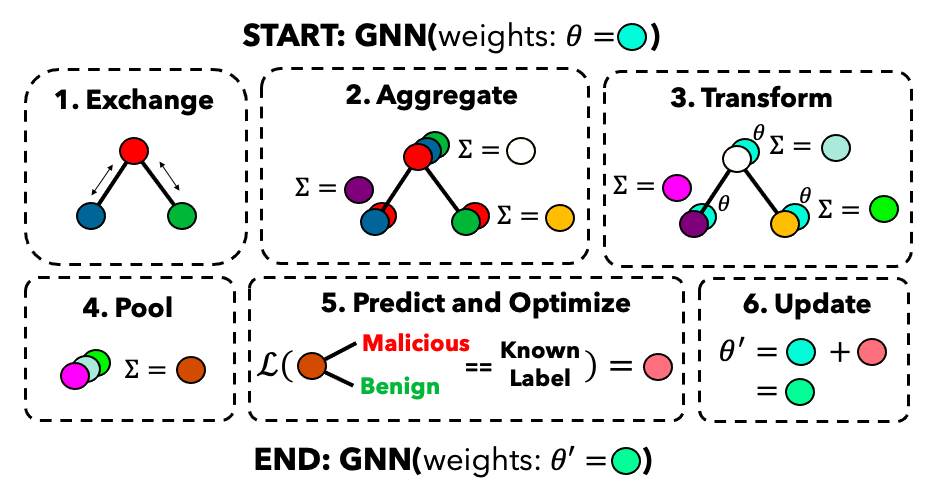

At an informal, non-technical level, GNNs work by repeatedly making tiny adjustments to a hidden program that seeks to understand a graph as the sum of neighborhoods around each node. Adjustments are made to the hidden program based on local estimations for how much each part contributes to the final prediction when it messes up. While not theoretically perfect, GNNs and neural networks have been found to achieve state-of-the-art performance on many tasks in practice.

At a semi-formal technical level, GNNs work by exchanging, aggregating, and transforming messages passed between all nodes and their respective neighbors. When combined with neural networks, GNNs are able to learn complex non-linear high-dimensional representations for a node with respect to its k-hop neighborhood by iteratively passing messages k times. When all node representations are pooled together, a representation for the graph can be derived that theoretically captures both the structure and behaviour of the entire program. This representation can then be passed to a classifier to make a final prediction.

Figure 1. GNN Flow Diagram

During training, these final predictions are compared to their known labels to derive the total loss . This loss is minimized via gradient descent to optimize the neural network with respect to each individual parameter or weight , via its partial gradients. The entire training process is repeated until a stopping condition is met, typically when loss converges to a minimum. A test set of reduced size is also commonly held out and evaluated to simulate inference performance on unseen samples. Common GNN architectures for this purpose include:

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) - Standard GNN for simple degree normalized message passing.

- GraphSAGE (SAmple and aggreGatE) - GNN using sampling to handle large graph sizes.

- Graph Attention Networks (GAT) - GNN that considers the influence of varying connections.

- Graph Isomorphic Networks (GIN) - GNN that favors expressive power for representing graph structure.

During inference, i.e., deployment, when the graph of an unknown sample is provided as input to the GNN model, prediction is performed using the same steps as in training but without optimization since the real label is unknown.

Advantages and Limitations of GNNs

While GNN methods excel in the malware detection setting, they also have many competitors from ML based methods that are often simpler and much faster. Although crucially, these ML-based methods often rely on features that can be trivially changed in an adversarial setting. Furthermore, they often do not provide appropriate levels of explanation related to a particular prediction. As such, a major advantage of GNNs is the ability to offer explanations at either the structural or feature level [5-7]. However, since GNNs are not intrinsically explainable, external models that probe the GNN post-hoc for sample-level importance must be used. Commonly used explainers for this purpose include GNNExplainer, PGExplainer, and Captum-based explainers such as Salience, Guided Back Propagation, and Integrated Gradients. Explanations at this level are also beneficial as they can help create explainable deep learning derived sub-graph signatures [8]. Thus, unlike traditional ML and signature-based detection methods, GNNs can help provide much-needed transparency in a high-risk malware detection setting.

However, even though the future of graph-based malware detection is promising, several limitations of GNNs exist. Notably, over-smoothing, adversarial evasion, graph size, and a limited number of available executable samples hinder training more adversarially robust and generalizable GNN models. Furthermore, both static and dynamic extraction of graphs can be extremely costly.

Conclusion

While existing works aim to address some of these issues, such as graph size [3, 4, 9] and graph dataset availability [5, 6], renewed commitment is needed to address the threat from sophisticated malware code generation systems that require intelligent defences that GNNs can provide.

Author Note

The author has chosen to exercise their right to affirm that this work was written exclusively by them, free from the influence or assistance of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) based tools. Only basic spell-checking and formatting tools, such as Microsoft Word and Grammarly, without GenAI capabilities, were used in the creation of this blog post.

This note is intended only as encouragement, from a near peer, for conveying original thoughts and ideas in written form without fear or judgement related to English writing style, quality, or typos. This encouragement is intended to relieve pressure on individuals to unnecessarily depend on GenAI in self limiting and harmful ways.

Footnotes:

- (i) To avoid confusion, we do not mention the case where benign signatures are also matched. However, the same problem of non-set membership attribution remains.

- (ii) While a non-zero hash collision probability exists universally for all hash-based comparisons, modern cryptographic implementations of sufficiently large hash space and pre-image resistance offer provably negligible collision probability under specific conditions and adversarial settings.

- (iii) Claims of “increased confidence” related to signature database quality and quantity are often made in practice to justify a sample type. However, such claims are extremely theoretically fragile, especially in an adversarial setting.

Edited By: Windhya Rankothge, PhD, Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity

Citations:

[1] J. Kornblum, “Identifying almost identical files using context triggered piecewise hashing,” Digital Investigation, vol. 3, pp. 91–97, Sept. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.diin.2006.06.015.

[2] ka1d0, “Fuzzy Hashing — ssdeep,” Medium. Accessed: Nov. 30, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://nikhilh20.medium.com/fuzzy-hashing-ssdeep-3cade6931b72

[3] H. Shokouhinejad, R. Razavi-Far, H. Mohammadian, M. Rabbani, S. Ansong, G. Higgins, “Recent Advances in Malware Detection: Graph Learning and Explainability,” July 22, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2502.10556. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2502.10556.

[4] H. Shokouhinejad, G. Higgins, R. Razavi-Far, and A. A. Ghorbani, “A Research and Development Portfolio of GNN Centric Malware Detection, Explainability, and Dataset Curation,” IEEE International Conference on Data Mining Workshops, Nov. 9, 2025. doi: 10.1109/ICDMW69685.2025.00126.

[5] H. Shokouhinejad, G. Higgins, R. Razavi-Far, H. Mohammadian, and A. A. Ghorbani, “On the consistency of GNN explanations for malware detection,” Information Sciences, vol. 721, p. 122603, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.ins.2025.122603.

[6] H. Mohammadian, G. Higgins, S. Ansong, R. Razavi-Far, and A. A. Ghorbani, “Explainable malware detection through integrated graph reduction and learning techniques,” Big Data Research, vol. 41, p. 100555, Aug. 2025, doi: 10.1016/j.bdr.2025.100555.

[7] H. Shokouhinejad, R. Razavi-Far, G. Higgins, and A. A. Ghorbani, “Explainable Attention-Guided Stacked Graph Neural Networks for Malware Detection,” Aug. 14, 2025, arXiv: arXiv:2508.09801. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2508.09801.

[8] H. Shokouhinejad, R. Razavi-Far, G. Higgins, and A. A. Ghorbani, “Enhancing GNN Explanations for Malware Detection with Dual Subgraph Matching,” Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, vol. 8, no. 1, Dec. 2025, doi: 10.3390/make8010002.

[9] H. Shokouhinejad, R. Razavi-Far, G. Higgins, and A. A. Ghorbani, “Node-Centric Pruning: A Novel Graph Reduction Approach,” Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction, vol. 6, no. 4, pp. 2722–2737, Dec. 2024, doi: 10.3390/make6040130.